Karl Marx once observed that history is shaped by a struggle between those who have and those who have not, between the owners of the means of production and the workers who sustain them. In the 19th century, the “means of production” were factories, land, and machinery. The Industrial Revolution transformed economies and societies, creating immense wealth for some while leaving countless others behind. Factories churning with coal and steam were symbols of human progress, yet they also exposed the stark inequalities of industrial life. Those who owned the machines shaped the rules, the wages, and the rhythm of life for the masses who worked for them.

Two centuries later, the means of production have shifted. The machines are no longer made of iron and steel. They are made of data, algorithms, and neural networks. Artificial intelligence now powers decisions that once required human judgment, from diagnosing diseases and analysing markets to designing products and even writing essays. The power to shape society no longer rests solely in factories, but in servers, cloud infrastructure, and access to sophisticated models. And yet, a familiar question arises: is AI creating a new kind of divide between those who can access, control, and shape it, and those who cannot?

Microsoft’s recent AI Diffusion Report shows that over 1.2 billion people have already interacted with AI tools. That makes AI arguably the fastest-spreading general-purpose technology in human history, reaching this milestone faster than electricity, the internet, or even smartphones. Yet adoption is not uniform. In countries like Singapore and the United Arab Emirates, more than half of working-age adults regularly use AI tools. In many economies across Sub-Saharan Africa, South Asia, and parts of Latin America, adoption rates remain below 10 percent. The same technology that can accelerate learning, business, and healthcare in some regions barely reaches others.

Across classrooms and workplaces, people are finding creative ways to use AI. Teachers in urban centres can translate lessons into multiple languages, design adaptive learning plans, and provide feedback that would have taken hours or days. Small businesses can automate customer service, analyse market trends, and scale operations far faster than traditional methods allowed.

Yet in regions with poor connectivity, unreliable electricity, or lack of computational resources, AI remains out of reach. Talented entrepreneurs and educators often face the same obstacles that workers in Marx’s factories once did, the tools exist, but the conditions to use them effectively are absent.

Power in Marx’s time rested with those who controlled factories. Today, power rests with those who control data, algorithms, and computational infrastructure. The modern “means of production” are digital. They include not only raw data, which fuels machine learning models, but also access to high-performance computing, internet connectivity, digital skills, and language representation. Microsoft identifies five key pillars that determine the spread of AI: electricity, computing infrastructure, connectivity, digital and AI skills, and linguistic inclusion. Each pillar is essential; the absence of any one can slow adoption, creating gaps between communities, cities, and nations.

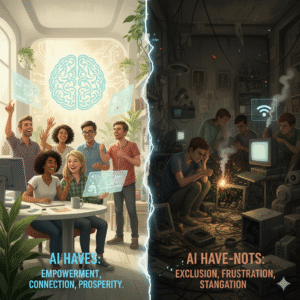

Those with access to these resources can leverage AI to innovate, teach, and grow businesses. Those without access are left on the periphery of this new digital economy. This emerging “AI divide” mirrors Marx’s original insight: inequality is not just about wealth, but about control over the tools that create opportunity. Today, the owners of digital capital, technology platforms, cloud providers, and data-rich institutions, wield influence over information, commerce, and even knowledge itself. Meanwhile, billions of people remain passive users of tools they cannot fully shape or understand.

Language adds another layer to this inequality. Most AI models perform best in high-resource languages like English, Mandarin, or French. Millions of people who speak African, South Asian, or Indigenous languages remain digitally invisible. Educators and community organizers often have to translate or adapt AI outputs manually, spending hours that others use to innovate, teach, or scale solutions.

In Kenya, for instance, mobile apps help farmers manage crops using AI-generated insights. Yet these apps often work best in English or Swahili, leaving local dialect speakers with limited utility. In rural India, teachers may use AI to create exercises in Hindi, but local tribal languages are not supported, forcing them to improvise. Language, like infrastructure, shapes who can participate in the AI revolution and who is left behind.

Geography also matters. In urban centres with stable electricity, fast internet, and cloud infrastructure, AI adoption accelerates naturally. Small startups in Singapore can scale operations globally within months, leveraging AI for market analysis and customer engagement. Meanwhile, communities in remote areas of Africa or South Asia may have talent and creativity, but face persistent barriers in connectivity and infrastructure, slowing their ability to use AI effectively. The geography of intelligence is no longer only about access to natural resources or industrial capital; it is about digital infrastructure and human skills.

Education and skill-building are crucial bridges across this divide. Digital literacy and AI fluency empower individuals to use AI responsibly and creatively, not just consume outputs passively. Regions that invest in teaching AI skills to youth, educators, and entrepreneurs are seeing faster adoption and more innovative applications. Inclusion is not charity; it is a strategic driver of innovation. When more people have the ability to participate, AI becomes smarter, fairer, and more relevant to the societies it serves.

The transformative potential of AI is enormous. In classrooms, personalized AI tutoring can help students learn at their own pace, identify gaps, and gain confidence. In healthcare, AI can triage patients, optimize diagnostics, and provide insights in regions where medical expertise is scarce. Small businesses can automate tedious tasks, analyse consumer behaviour, and compete in ways previously impossible.

But the promise of AI is unlocked only when foundational barriers, infrastructure, skills, and language, are addressed. Otherwise, the technology amplifies existing inequalities, creating a new hierarchy of haves and have-nots.

Two centuries ago, industrial machines reshaped society. They created wealth, opportunity, and profound inequality. Today, AI is reshaping work, creativity, and learning, only faster and more globally. Unlike in Marx’s time, however, we now have awareness and the tools to influence outcomes. We can choose to build inclusion into AI systems from the start, rather than patching inequality afterward. Access to energy, connectivity, digital literacy, and language support are not peripheral considerations, they are the new foundations of opportunity.

The human thread remains central. AI may process data, but it is humans who interpret meaning, solve problems, and create value. The most profound innovations will emerge not from the largest servers or the wealthiest corporations, but from communities that are empowered to use AI imaginatively and collaboratively. From educators designing lessons in local languages, to farmers using mobile apps for crop management, to small entrepreneurs scaling businesses globally, AI’s potential multiplies when more people have access.

The Industrial Revolution taught us that technology alone does not guarantee progress for all. Wealth and opportunity flowed primarily to those with control over the machines. The AI revolution could repeat this pattern, but it doesn’t have to. We can build systems that ensure equitable access, nurture talent, and respect linguistic and cultural diversity. By consciously embedding inclusion into AI’s foundation, we can make it a bridge rather than a barrier.

The question is not whether AI will transform the world, it already has. The question is who will participate in this transformation. Will it remain concentrated in the hands of a few, or will its power be shared broadly? If we prioritize access, skills, and inclusion, AI can become a force that amplifies human creativity, accelerates learning, and enables communities to solve problems that matter most to them.

Marx’s class divide was rooted in industrial machinery. The divide today may be digital, but it is no less real. The challenge of our time is to ensure data, algorithms, and AI models are not just the privilege of the few, but tools for the many. Because in the end, progress is not measured by machines, but by how we choose to use them to improve lives, foster opportunity, and share intelligence across the globe.

If we get this right, the story of AI will not be about who owns the algorithms. It will be about who has the opportunity to learn, create, and innovate, about how curiosity, imagination, and access converge to shape a fairer and more connected world. AI can be the bridge which Marx envisioned for society: a technology that amplifies human potential and narrows the gap between the haves and the have-nots, rather than widening it. It can transform not just economies, but lives, education, and the very fabric of society, if we deliberately build inclusion into its foundation.

Note: Based on data and insights from Microsoft’s AI Diffusion Report. Images are created using AI.